| Hormone | Effects |

|---|---|

| Cholecystokinin (CCK) | Released in the small intestine when fats and proteins are eaten. Receptors that respond to CCK are not only found in the gut but also in the brain. In the brain CCK depresses hunger, meaning the more CCK you have floating around the less hungry you are, and the less you’re likely to eat. This is why a lower-carb, higher-protein, higher-fat diet tends to make people feel fuller longer. |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) |

Delays stomach emptying time that may make you feel more full. |

| Gastric inhibitory polypeptide YY (PYY) |

Secreted by small bowel and colon in response to food. Inhibits hunger. |

| Leptin | Mostly released by fat; decreases hunger. If you want to lose weight you’d want to have more leptin. |

| Ghrelin | Made mostly in the stomach; acts on the brain (hypothalamus) to stimulate hunger. If you want to lose weight, you want less ghrelin. |

- 604-362-9571

- Monday - Sunday

Blog

Talking Cheat Days, Hormones and Fat Loss via Precision Nutrition

- by Michelle

- October 8, 2018

Lately I have been having a lot of chats with clients about allowing themselves cheat days, I know sounds weird right? A weight loss trainer telling their clients to eat unhealthy food??

Believe it or not one cheat meal for weight loss per week is actually imperative to raising metabolic rate and successful fat loss, isn’t this the best news EVER!!

Here are the 3 main reasons for cheat days:

Increased thyroid hormone output– When in a caloric deficit, underfed individuals produce less T3 and T4–both important thyroid hormones that play roles in the regulation of metabolic rate. A cheat day or strategic overfeed is used in part to increase these hormones.

Increased 24-hour energy expenditure– A caloric surplus from a cheat day causes the body to upregulate basal metabolic rate (BMR). Some studies have shown an increase of 9% above baseline, and it’s hypothesized that more is possible.

Increased serum leptin levels– The big one that most harp on. Leptin levels drop while in a caloric deficit (lasting as little as 72 hours), and a periodic bump in leptin coming from a cheat day has several benefits including increased thyroid output, increased energy expenditure and BMR, and overall increased thermogenesis.

BUT WAIT:

Be careful with the difference between cheat meals and cheat days because the leaner you are the more you can get away with. For example, if you have 40 + pounds to lose you should try and limit yourself to only 1 cheat meal per 1 – 2 weeks. If you are not eating at a large caloric deficit (50 or less calories/day) then a cheat day/meal is not necessary, but given you are eating very strict and clean 5-6 days per week then pick one day a week to increase your leptin levels (see above) and endulge! Keep your cheat meal Plan for weight loss from 500-800 calories and be careful not to go too overboard! One last thing…..to get the most out of your weekly cheat meal, try to have it within a few hours after a workout!

Don’t Believe Me?? Check out the two articles below from my nutrition certifying body Precision Nutrition

Study #1:

Fast weight loss & hunger hormones Research Review

Why “willpower” may not be your problem

Short-term very-low-calorie dieting disrupts powerful hormones that control appetite, hunger, and satiety for up to a year after a strict diet. Crash diet now, feel hungry later… even several months later.

What is the top New Year’s resolution? Lose weight.

Every year, people with good intentions set out to lose weight, only to have even more weight to lose the next year later. (Resolutions seem like such a good idea when you’ve got a party horn in your hand and a gold cardboard top hat on your head, swimming in a champagne-induced fog.)

One problem is that people try to lose weight quickly. Unfortunately, even if they manage to drop a few pounds fast, they bounce right back… and often, keep on gaining.

Now, research confirms our methods. (But we knew that already.) Only slow and steady progress leads to lasting change. Why?

Appetite hormones: Why self control is not the problem

Myth: weight loss is all about self control.

People berate themselves or are judged by others for carrying a few extra pounds. To be fat means you’re weak-willed, spineless, and/or impulsive.

Fact: Powerful hormones control our perception of appetite and hunger, as well as our eating behavior.

While you still have the option of self-control, your body definitely has a strong voice in the matter. And “willpower” breaks down easily under stress; when blood sugar is low; and/or in environments that don’t support weight loss (like an office where everyone has a candy dish and it seems like someone has a birthday cake every day).

Here are some of the more well-known hormones that influence appetite, hunger, and satiety.

The ideal hormone combo to suppress appetite and help you lose weight would be:

- more CCK, GLP-1, PYY, and leptin

- less ghrelin

What happens to hormones over the long haul?

The study I’m reviewing this week looks at what happens to appetite hormones after 10 weeks of dieting up to 1 year later. Yup, your lemon-cayenne diet from last year may be making you feel more hungry this year.

Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A, Proietto J. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct 27;365(17):1597-604.

Methods To Control Diet Calories

This year-long study involved 50 people with BMI between 27 and 40 (classified as overweight and obese), who went on a crazy low-calorie diet for 10 weeks (though the researchers called it a very-low energy diet).

What’s a crazy low calorie diet? Oh, say 500-550 kcal for people that had an average weight of 95 kg (209 lb), which is one-third of their basal metabolic rate. To live without moving at all, these volunteers would need about 1700 kcal on average. No question they were really hungry and needed a hell of a lot of will power to stay on this diet.

The problem with calorie math

Basal metabolic rate

BMR is the amount of energy you need to live when at rest. The most common equation to calculate BMR is the Harris-Benedict equation.

BMR calculation for men

BMR = 66.5 + (13.75 x weight in kg) + (5.003 x height in cm) – (6.755 x age in years)

BMR calculation for women

BMR = 655.1 + (9.563 x weight in kg) + (1.850 x height in cm) – (4.676 x age in years)

This intake of 500-550 kcal means that each day these volunteers are eating at least 1200 kcal less than they need.

Since fat has 3600 kcal/pound, you could use basic (and flawed) calorie counting to figure they should lose a pound (0.45 kg) of fat every three days. At the end of 10 weeks (70 days) they should lose just over 23 pounds (10.6 kg), or 11% body weight in fat.

The problem with thinking of yourself as just fat that’s burned like a candle is that you overlook things like hormones that through evolution respond to starvation by storing calories more efficiently.

A few hundred years ago, it was a good thing that your body responded to starvation by storing as much fat as possible. Thrifty hormones saved lives. Now when starvation is self-induced in a sea of food it causes problems.

Results

During the first 10 weeks of the study, when the volunteers were eating a very low calorie diet, they lost 9.4 kg (20.7 lb) of fat and 4.1 kg (9 lb) of lean body mass, but that didn’t last over the next year.

As the year went on after the diet, they slowly gained half the weight they lost. At first glance, that doesn’t sound too bad. They lost a fair bit of weight in a short period, and then a year later, they were still ahead of the game.

Hormonal effects: short term

The problem is what happens to these volunteers’ hormones — the hormones like leptin, ghrelin, peptide YY, etc. — that regulate appetite, hunger, and satiety.

After 10 weeks of starvation the volunteers had less leptin, peptide YY, and cholecystrokinin, as well as more ghrelin and gastric inhibitory polypeptide. The result: The volunteers felt more hungry. Cue the need for even more will power to keep the weight off. Sound familiar?

Hormonal effects: long term

We knew that crash dieting messes up appetite regulatory hormones for a short period, but until now, nobody had looked at the long-term effects of very low calories on these hormones.

Why didn’t anyone look at what happened a year or more later?

Well, it’s hard to get people signed up for a year-long anything, let alone having them go on a starvation diet for over two months first. Plus, it’s a bit of a surprise that a short term diet would do much a year later. These scientists must have had to convince a lot of people that this study was worth doing.

One year after dieting the volunteers still had less leptin, peptide YY, and cholecystokinin; and more ghrelin, gastric inhibitory polypeptide and pancreatic polypeptide.

What happened to hunger? Still higher after a year. Think about that. A full year after dieting, the volunteers still felt more hungry. No surprise that most dieters regain weight lost and more… eventually.

Conclusion

If you try to lose weight quickly, you’ll end up trying to lose it every year instead of taking a year to lose the weight once.

It’s clear that very low calorie dieting has long term impact on hunger and appetite hormones lasting at least a year. Now imagine what multiple crash diets might do.

By the way, stringent and chronic restriction also affects hormones that control gastric motility (the speed at which food is processed) and neurotransmitters (brain chemicals).

Thus, if you regularly “diet”, not only do you end up always hungry, you have indigestion and “brain hamsters” like anxiety or depression, and you rarely feel psychologically satisfied by eating — you always want more, or have strong cravings. Show me a “professional dieter” and I’ll show you someone who feels generally lousy physically, mentally, and emotionally. Hormonal disruption is strong stuff.

Could yo-yo dieting lead to cumulative changes in appetite regulation hormones? Very likely. Several years of yo-yo dieting later, you may feel much more hungry than when you started. Good luck with willpower then.

Bottom line

Lose weight quickly while nearly starving, only to gain most of it back (or more) and feel hungrier than when you started. Or lose weight slowly, for good, and feel better than ever… eventually.

STILL NOT CONVINCED???

Study #2:

Research Review: Leptin, Ghrelin, Weight Loss – It’s Complicated

It’s a grim statistic: Most people who go on a diet and lose weight end up regaining that weight within a year.

Doesn’t sound too promising.

Why does this happen? Well, there are many reasons.

The big one is that people view a “diet” as a short-term solution and don’t really change their behaviours

Another reason is that our bodies have appetite- and weight-regulating hormonal mechanisms that try to maintain homeostasis (aka keep things the same) over the long haul. When we consistently take in less energy (in the form of food) than we expend through basal metabolism and activity (as in a diet or famine), our bodies respond by making us hungrier.

Our bodies don’t generally want to change. They like everything to stay the same. If we try to change things, our bodies will respond with compensation mechanisms, such as revving up our appetite hormones.

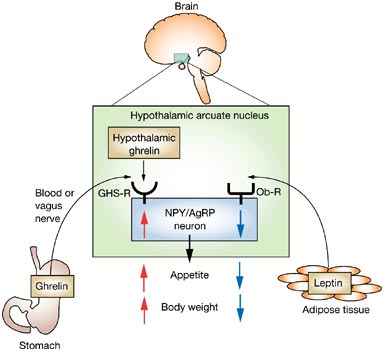

Two important hormones that shape our appetite and hunger signals are leptin and ghrelin.

Hormonal control of appetite and body fat

Leptin and ghrelin seem to be the big players in regulating appetite, which consequently influences body weight/fat. When we get hungrier, we tend to eat more. When we eat more, obviously, we maintain our body weight or gain that weight back.

Both leptin and ghrelin are peripheral signals with central effects. In other words, they’re secreted in other parts of the body (peripheral) but affect our brain (central).

Leptin is secreted primarily in fat cells, as well as the stomach, heart, placenta, and skeletal muscle. Leptin decreases hunger.

Ghrelin is secreted primarily in the lining of the stomach. Ghrelin increases hunger.

Both hormones respond to how well-fed you are; leptin usually also correlates to fat mass — the more fat you have, the more leptin you produce. Both hormones activate your hypothalamus (a part of your brain about the size of an almond).

And here’s an important point: both hormones and their signals get messed up with obesity.

Leptin

Back in 1994, researchers noticed that one genetically altered strain of mouse ate a lot and was obese. When researchers administered a new substance, leptin (from leptos, or “thin” in Greek), the mice lost weight.

Soon after, nearly everybody interested in fat research was doing research on leptin.

At the time this was the holy grail of obesity research: a protein that made really, really fat mice into skinny mice. Fantastic! We’ll just make leptin pills, and everyone will be ripped, including the mice.

Well, like most things in biology, leptin is more complicated than that.

As it turns out, leptin injections only worked on mice (and people) who were genetically leptin deficient — only about 5-10% of obese subjects. The other 90-95% were out of luck.

How does leptin work?

Leptin is made by adipose tissue (aka fat) and is secreted into the circulatory system, where it travels to the hypothalamus. Leptin tells the hypothalamus that we have enough fat, so we can eat less or stop eating. Leptin may also increase metabolism, although there is conflicting research on this point. (1)

Generally, the more fat you have, the more leptin you make; the less food you’ll eat; and the higher your metabolic rate (possibly). Conversely, the less fat you have, the less leptin you have, and the hungrier you’ll be.

Basically, for weight loss — the more leptin the better.

Leptin resistance

You’d think, then, that fatter folks would somehow magically stop eating or start losing weight once their leptin levels were high enough. Unfortunately, you can become leptin resistant (2).

In that case, you can have a lot of fat making a lot of leptin, but it doesn’t work. The brain isn’t listening. No drop in appetite. No increased metabolism. Your brain might even think you’re starving, because as far as it’s concerned, there’s not enough leptin. So it makes you even hungrier.

It’s a vicious cycle.

- Eat more, gain body fat.

- More body fat means more leptin in fat cells.

- Too much fat means that proper leptin signalling is disrupted.

- The brain thinks you’re starving, which makes you want to eat more.

- You get fatter. And hungrier.

- You eat more. Gain more fat.

- And so on.

Leptin resistance is similar to insulin resistance (and they also share common signalling pathways). Insulin resistance occurs when there’s lots of insulin being produced (for example, with a diet high in sugar and simple carbohydrate), but the body and brain have stopped “listening” to insulin’s effects.

Interestingly, both types of resistance seem to occur together in obese people, though obese men who tend to have more internal belly fat (visceral fat) have higher insulin levels, and women who tend to have more fat under their skin have higher leptin levels (2).

Another leptin resistance fun fact is that fructose seems to induce leptin resistance (3).

There are a few possible explanations for how leptin resistance actually works. One theory is that leptin can’t get to the hypothalamus because the proteins that transport it across the blood brain barrier aren’t working or aren’t there, since there’s a buildup of leptin in the cerebral spinal fluid that bathes the brain (4).

Regardless of the actual mechanics, the important point here is that past a certain level, having more body fat can screw up your appetite signals and actually make you hungrier.

Ghrelin

Ghrelin was discovered 7 years after leptin, but after the leptin letdown, there was much less fanfare.

Leptin is a hormone that is a result of a buildup of fat, so it’s a long term regulator of body weight. Meanwhile, ghrelin is the short term Hey I’m hungry when do we eat? regulator.

Your stomach makes ghrelin when it’s empty. Just like leptin, ghrelin goes into the blood, crosses the blood-brain barrier, and ends up at your hypothalamus, where it tells you you’re hungry (1,5).

Ghrelin is high before you eat and low after you eat.

If you want to lose weight you want less ghrelin, so you don’t get hungry. If you want to gain weight, say if you’re scrawny, then you want more ghrelin — or at least you want it to stay high as you eat, so you’ll want to eat more.

Both hormones, as I mentioned, regulate appetite and hunger, and both of them regulate homeostasis — in this case, keeping you adequately fed. When you try to lose fat, your body will probably respond by changing hormone levels so that you get hungrier.

Obviously, this presents a challenge for folks trying to lose fat and keep it off — leading, perhaps, to the dreaded “yo-yo dieting” phenomenon.

Research question

Can leptin and ghrelin levels provide some explanation for the ups and downs that dieters experience? And could this relationship be more complicated than we expect?

This week’s review looks at how leptin and ghrelin levels are related to weight regain after dieting. (The title kind of gives the punch line away.)

Crujeiras AB, Goyenechea E, Abete I, Lage M, Carreira MC, Martínez JA, Casanueva FF. Weight regain after a diet-induced loss is predicted by higher baseline leptin and lower ghrelin plasma levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Nov;95(11):5037-44. Epub 2010 Aug 18.

Methods

Researchers put over 160 obese and overweight men and women with an average BMI over 31.1 kg/m2 on a calorie restricted diet for 8 weeks.

This diet was 30% less (500-600 kcal/day) than the participants’ total energy expenditure, with 15% of calories from protein, 30% from fat and 55% from carbohydrates. There was no change in physical activity, just less food.

Researchers measured body weight, body fat and waist girths. They also took blood samples. Measures were taken before dieting (week 0), right after the dieting (week 8), and 6 months later (32 weeks).

Results

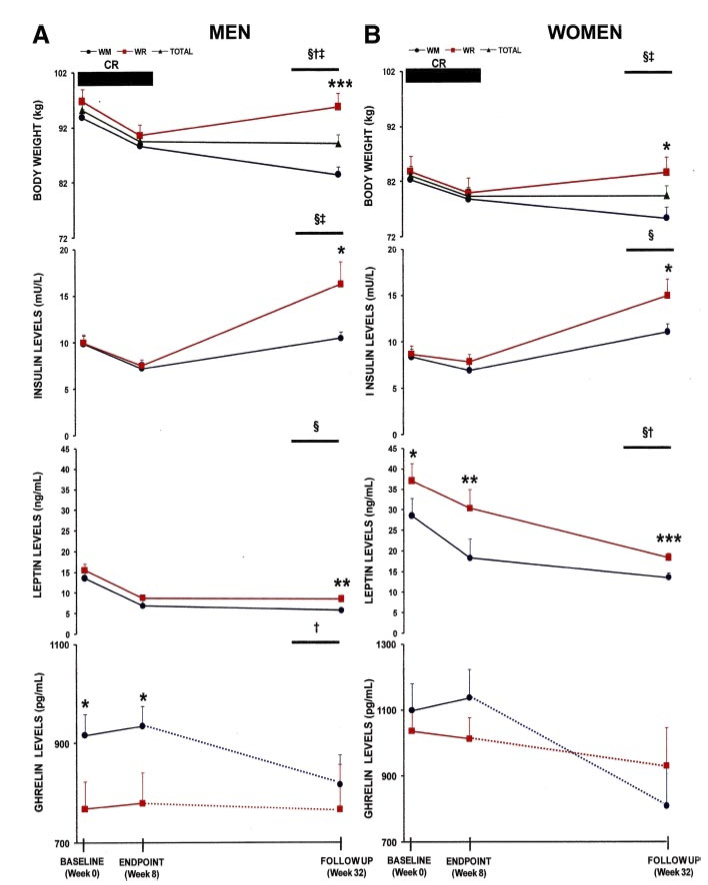

After 8 weeks on the diet, people lost an average of 5% body weight. Men lost 5.9% on average, and women lost 4.5%. They lost an average of 1.6% body fat and 4.1 cm off their waists.

Gainers and losers

But the average doesn’t give us the whole story. Some folks lost more than 5% of their weight, while others lost less. This may seem self-evident and not that interesting… until you look at their blood samples.

Dieters who lost more weight (>5%) had a bigger drop in leptin and insulin compared to dieters who lost less weight (<5%). Somehow losing weight is correlated to drops in leptin and insulin.

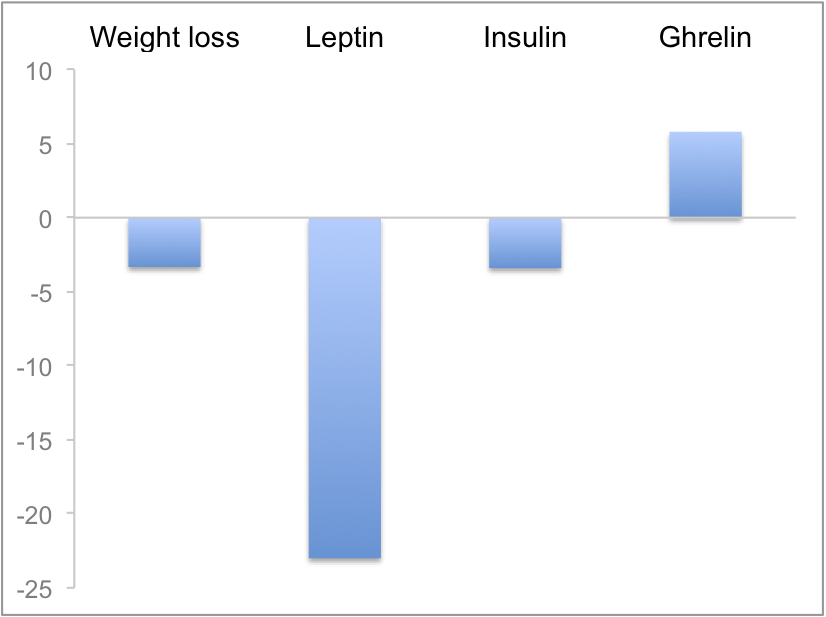

Figure 1 below compares the differences between the two groups. Compared to the <5% weight loss group, the >5% weight loss group:

- lost more weight (obviously)

- had lower leptin levels

- had lower insulin levels

- had higher ghrelin levels

This is pretty much what you’d expect.

Six month after the diet ended, this split continued. About half the group lost more weight; half the group re-gained the weight they lost.

Blood levels of leptin and ghrelin were correlated to weight loss or regain — and this effect often depended on sex.

- Women with lower blood leptin at the end of dieting were more likely to maintain their weight loss, but ghrelin didn’t seem to make a difference.

- Men with higher ghrelin levels at the end of dieting were more likely to regain weight, but leptin didn’t seem to matter.

- For both men and women, insulin levels at the end of dieting didn’t seem to matter in the long term, although insulin levels did increase when weight went back up.

- For both men and women, ghrelin levels were higher (meaning they were hungrier) at the end of dieting, but in weight losers, ghrelin levels dropped.

Huh.

Figure 2 shows the changes in hormone levels between weight maintainers (WM) and weight regainers (WR) at the start of the diet (0 weeks), end of the diet (8 weeks), and 6 months later (32 weeks). WRs are indicated by the red lines; WMs are the black lines with circles.

Discussion and Conclusion

The biggest hurdle dieters face is weight regain — and dealing with it is a daunting prospect.

Appetite is controlled by a host of complex, interacting factors. This study suggests that the hormonal mechanisms may be different for men and women — and among men and women.

This difference may reflect the different hormonal environments in men and women. For instance:

- Ghrelin seems to be affected by growth hormone release, which differs in men and women.(6)

- Leptin seems to influence reproduction and fertility in women, which is related to women’s body fat levels. Women appear to be much more sensitive than men to leptin levels… unless men are given estrogen.(6)

- Intranasally administered insulin makes men less hungry and lose weight, but makes women hungrier and gain weight… unless women’s estrogen levels, or men’s testosterone levels, are low.(6)

However, there were also important differences within groups as well. Some men lost weight while others regained it. Some women lost weight while others regained it.

As the researchers point out, these findings suggest “the existence of two different populations according to the leptin and ghrelin levels [are] influencing the response outcomes”.

We’d expect that folks who regain weight easily would have lower leptin and higher ghrelin — making them hungrier. Not so in this study. The researchers propose that these results “are consistent with a disruption in the sensitivity to these hormone signals, probably in the central nervous system of those subjects with a higher predisposition to regain body weight.”

This suggests that in obese people, leptin and ghrelin signals may not always work in ways that we expect. Obesity can disrupt normal appetite signalling.

There is probably more to the story, and we’ll need more research to understand all the elements of weight loss.

Many factors in weight loss

Thus it appears that there are many important factors that shape successful weight loss.

If you’re looking for the silver bullet that will magically kill hunger and strip body fat off you, give up now.

Metabolic endocrinology appears to be only slightly more complicated than a nuclear reactor and brain surgery combined. No single hormone controls body composition, appetite, and hunger — and your individual hormonal profile may be relatively unique.

What’s also notable is that dieters who lost more weight on the diet had more significant changes in their appetite. They were probably hungrier while losing that weight.

Does the diet matter?

A few things that likely are contributing to weight regain are that this was a diet. Reduce calories for 8 weeks, lose the weight, then hope things work out for you. Obviously since it worked for some people, this method has some merit.

But as the data show, short-term diets alone don’t have a great success rate in the long run.

The macronutrient breakdown of this diet could also be relevant. It’s relatively low in protein, moderate in fat, and high in carbohydrate. We might see different hormonal effects with, say, a low-carb, high-fat, high-protein diet.

What else can I do?

Strictly looking at improving ghrelin and leptin levels, some studies have shown that taking fish oil and getting regular sleep help. (7-9)

Other factors that help long term weight loss include:

- increased physical activity

- getting social support

- behaviour change techniques (e.g. goal-setting) (10).

Bottom line

Many interacting hormones shape our appetite and hunger. Several factors affect these hormones and our response to them. So if you’re looking for a single solution — or rely on a short-term diet as a quick fix — you’ll probably be disappointed.

But there’s good news: There are many things that you can do that will lead to lasting body composition change.

- Take fish oil. Omega 3 fatty acids are linked to decreased hunger. (7)

- Sleep. Lack of sleep leads to more ghrelin and less leptin, as well as disrupted glucose and insulin metabolism. (8,9)

- Don’t get discouraged by these kinds of studies. Other research shows that it is possible to lose weight and keep it off — you just have to do a bit more than pop a leptin pill or do a few jumping jacks. The National Weight Control Registry tracks the features of successful losers. These include behaviour change, a commitment to good nutrition, and regular exercise.

- Understand that when losing fat, you might be hungrier. That’s normal.

Email Michelle@CORE-Condition.com if you have any questions or visit the Precision Nutrition Website for more helpful information!